Today Sally at Smorgasbord posts her review of my first novel Quarter Acre Block. Thanks Sally.

Today Sally at Smorgasbord posts her review of my first novel Quarter Acre Block. Thanks Sally.

Many of us have been watching a new BBC Sunday evening drama, Ten Pound Poms, prompting friends to ask how it compared with my family’s experience. The brief answer is completely different and I have found myself being irritated by some aspects of the series, not enough to stop me watching it though! In the drama it is the 1950s and the characters sail out to arrive in Sydney six weeks later, six seconds later for viewers. They are taken on a bus to a migrant camp, winding through bushland till some Nissan huts hove into view. My first annoyance was we had no idea how far away from Sydney they were, all it takes is for a character to say ‘blimey, a hundred miles from the city…’

Anyway, there they were with Nissan huts, dreadful looking outside ‘dunnies’ ( toilets ) and shower blocks. My running irritation is that one of the main characters, Kate the nurse, has make up more suited to modern reality shows or a girls night out. Her eyebrows are ridiculous and in the Australian heat her makeup would be running down her face, not that matron at the hospital would have allowed her to wear such makeup!

The Australians they meet are mostly awful, but so are some of the migrant characters; there are a lot of running stories packed in to this series. They seem to be in the middle of nowhere, but also near a country town, a hospital, the sea and some very swanky houses. What themes do ring true in this drama are the treatment of the Aborigines, who were not counted as humans in the census till the 1960’s and the fact that English children were sent out to Australia as orphans, but many had parents who didn’t know where they had gone.

Perth, Western Australia in the 1960’s

My family’s story is not as dramatic, for any of you who are watching the television series. It took Mum and Dad only six months from the time of applying to us all getting on a chartered migrant flight at Heathrow in October 1964. They chose Perth, Western Australia and we had a ‘sponsor’ who was a chap Dad knew ‘from the office’, the two families had never met. He met us at Perth airport at 1am and took us to the caravan he had booked for us. A week later my parents had found a house to rent. If we had needed to go to a migrant camp I’m sure my mother would not have stepped on the plane! By Christmas they had bought a house on a quarter acre block in a new suburb. Migrants were told that all houses were built on a quarter acre block, that idea didn’t last, but our house had natural bushland.

My novel Quarter Acre Block is inspired and informed by our family’s experience, but not autobiographical. It is told from the point of view of the daughter, who may have some similarities to me… and of the mother. Mum helped me with the adult experience point of view. In the rented house in an older suburb Mum said the only neighbour who talked to her was Dutch, but at our new house we quickly became friends with our new neighbours, who were dinky di Aussies from the goldfields of Kalgoorlie.

The lifestyle migrants looked forward to..

We knew little about Aborigines, I guess we assumed they were enjoying their lifestyle out in ‘the bush.’ We knew nothing about migrant children and stolen Aboriginal children being abused in orphanages.

‘In the nineteen sixties many ‘ten pound pommies’ had never left England before and most expected never to return or see loved ones again. George Palmer saw Australia as a land of opportunities for his four children, his wife longed for warmth and space and their daughter’s ambition was to swim in the sea and own a dog. For migrant children it was a big adventure, for fathers the daunting challenge of finding work and providing for their family, but for the wives the loneliness of settling in a strange place.’

Only 99 pence to download to Kindle or buy the paperback for ten pounds.

Have you been watching Ten Pound Poms, or have you or your family had experience of migrating to another country?

We were on a college summer camp on Rottnest Island in the middle of the Indian Ocean, well only 18 kilometres from Fremantle, Western Australia, but one of the girls had to be airlifted off by helicopter as she had heatstroke. Happy days – when we emigrated to Australia in 1964 nobody worried about skin cancer or staying hydrated. Fortunately my parents were aware the sun was hot. Dad was out in Egypt after WW2 before he was demobbed and told of ’idiots’ being stretchered out with third degree burns after sun bathing. Fortunately my parents avoided the beach after being taken to Scarborough Beach by our sponsors on our first day in Australia. Huge waves and hot sand did not appeal and we went to pleasant shady spots by the River Swan.

Unfortunately school outings were gloriously free of sun hats and sun lotion and I recall an early outing when we spent the whole day on the beach and next day my nose peeled and bled! Outings with youth groups on hot days were often followed by me feeling sick the next day; setting off without any money and probably a picnic with a plastic bottle of cordial, I obviously didn’t drink enough. At school we did have plenty of water fountains, I didn’t spend my whole time dehydrated, but my sister recalls that if you were thirsty when you were out you stayed thirsty. I’m sure other people were buying bottles of coke and cool drinks of lurid colour, but we were not.

Our current heatwave has brought endless dire warnings of the dangers of going out – or staying inside homes not designed to cope with hot weather. Modern parents never let their children out without a bottle of water, but they should not panic – if Prince George could sit in the heat of Wimbledon dressed in a jacket and tie there is no need to pamper children.

…and Which, Wonder, Winter, Widowhood, Worries, Will???

In French the Questions will be Quand, Quoi, pourQuoi…

Most of the world is asking when the pandemic will end and a further multitude of questions about variants and mutations, with no straightforward answers. Ironically, while England is still deciding whether to quarantine people in hotels, Perth, Western Australia detected its first case of coronavirus in almost 10 months; a quarantine hotel security guard. Nearly two million residents were placed into a five day lockdown on Sunday.

One thing most of us in lockdown don’t have to worry about is summer bushfires. Thousands were told yesterday and today to ignore the Covid stay-home order and evacuate their homes, as a bushfire in the hills on Perth’s outskirts gained pace. But the most chilling warning is It’s now too late to leave, you must stay in your home. The blaze, which is the largest the Western Australian city has seen in years, has already burnt through more than 9,000 hectares, destroying at least 71 homes.

Perth spotted one little weak spot in its robust Covid protection status, while many of us see great gaping holes in our countries’ defences. Hindsight is a great thing, but I think medical experts and even ordinary folk had enough foresight to see more should have been done earlier. There are people who have isolated completely for nearly a year, but most of us, every time government advice eased off, have had visitors or been on a little outing; some people have been jetting all round the world.

If you listen to the news too often you will drown in numbers and go round in circles. But one positive thing is the vaccination programme in the United Kingdom, which is rattling along at a great pace. With little new to talk about in lockdown, the gossip is who has been immunised lately.

What is everyday life like now after months of Tier systems, November Lockdown 2 and a month in Lockdown 3? Grandparents have been unable to see new grandchildren; weddings, moving home and plans to have babies have been put on hold all round the country. I have been widowed for five months now and half of me is still happy for normal life to be suspended, but the other half is missing family and friends and being able to visit and get out and about. Then there are the not so regular events that can’t take place; luckily Cyberspouse said he didn’t care what we did with his ashes, so he wouldn’t mind that they are still in the cupboard with all his camera equipment…

Going for walks is now the national occupation. I don’t drive, so I am used to walking to get places. Then there is the traditional going for a walk with your partner, family, friends or by yourself to recover from a stressful week at work. Whether locally or on a day out, The Walk used to involve stopping for coffee at a beach front café, lunch in ‘The Stables’ at a National Trust property or popping into interesting shops in that nice town by the river…

In lockdown you may get a takeaway coffee when you meet up with the one person from another household for exercise if you are living on your own. I am too dyspraxic to walk, talk, avoid tripping over dogs and drink out of a hot cardboard cup at the same time. But it is good to be out seeing people. The cliff tops and promenades are full of folk and plenty of those are also taking brisk walks by themselves, though I am the only one in a bright pink coat. Most of us are managing to adhere to social distancing and I think it is safe out in the fresh air or gale force winds.

A walk around residential streets as it’s getting dark is also quite fun; lights are on but curtains and blinds are still open. I have always enjoyed looking in people’s windows, all the different decors and cosy interiors and life going on. Some people still have Christmas lights in the front garden or Christmas trees indoors, it all helps brighten up this strange winter.

When we are not out, many of us are on line. Those of you working from home or trying to teach home schooled pupils are probably heartily sick of Zoom, but it’s still a novelty for me. We could all be in space ships or in a space colony. Is this the future? At the weekly Saturday evening quiz I see people I would never meet in real life. I have started going to our camera club Zoom meetings and members can put their pictures on the screen – not me obviously, my technical skills only stretch as far as typing in the meeting code – but it is nice to chat and see both familiar and new faces. Lounging on the sofa with my ipad instead of sitting on a plastic chair in the church hall, what’s not to like? Will people want to go out on dark winter evenings when they could just stay home? Those who are not on the internet or are nervous of technology could miss out, but the disabled, those who can’t leave children and those without easy transport would all be on an equal footing in Zoomland. Will this be what we wish for?

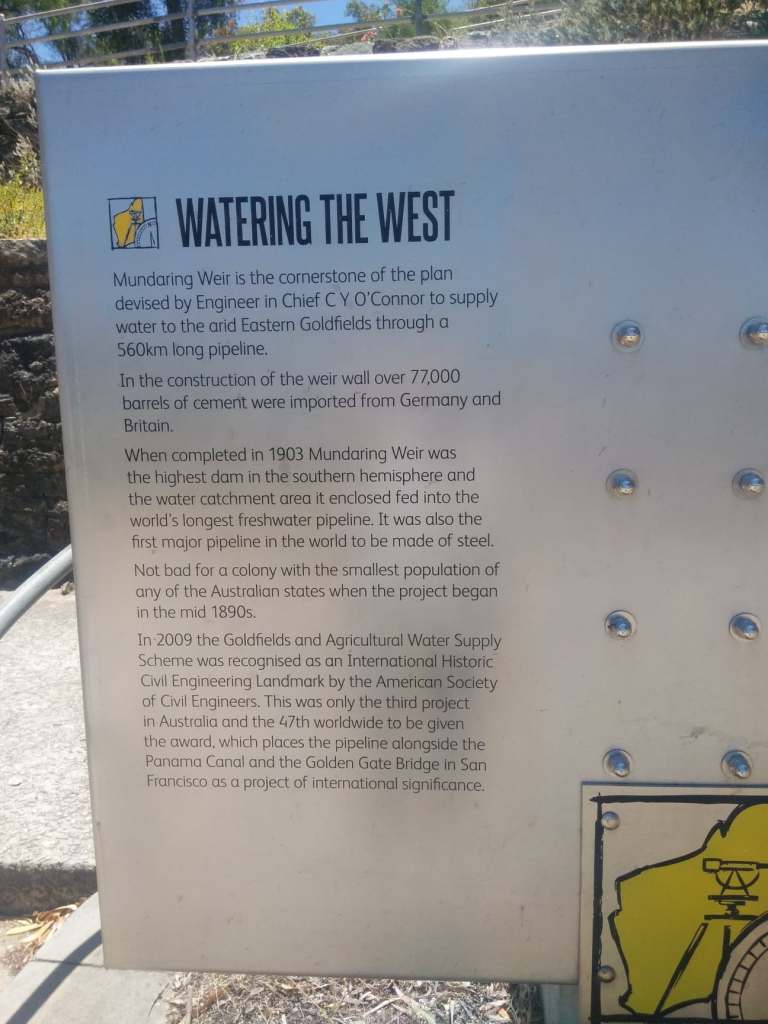

Today I welcome another guest blog by my sister in Australia. When our family first emigrated to Perth in 1964, going up in the hills to see Mundaring Weir overflowing was a regular outing…

Pipe Dreams by Kate Doswell

As a child, I was both fascinated and saddened by the story of Charles Yelverton O’Connor – always referred to as C. Y. O’Connor. As Western Australia’s Chief engineer at the turn of the last century, he was responsible, amongst other things, for the design and construction of Fremantle Harbour, WA’s main shipping port and – more famously – for the Kalgoorlie pipeline.

Kalgoorlie was the scene of WA’s massive gold rush and by the early 1900s was a busy town; the engine for much of the wealth and development of the fledgling state. The drawback was that it was in an arid area 560 isolating and harsh kilometres from the capital city of Perth. Supplies of water were a major stumbling block to further development and an answer needed to be found.

C. Y. O’Connor had the audacious idea to build a pipeline to take water from Perth to Kalgoorlie, a feat never attempted before over such a large distance. It would involve construction of a large dam at Mundaring, in the hills above the swan coastal plain. The project would require pumping stations at Mundaring and along the route, and steel pipes big enough to carry sufficient water.

It is ultimately a story of triumph – a brilliant idea, carefully planned and skilfully executed, a triumph made even more incredible considering its achievement by a small, isolated European settlement transplanted into an ancient country only 70 years before. But it is also a sad story. C. Y. O’Connor never lived to see its success; he committed suicide. The story I heard as a child was that the tap was turned on at Mundaring, but due to a miscalculation the water took longer than expected to reach Kalgoorlie. C.Y. O’Connor thought he had failed. He rode his favourite horse out into the surf at a Perth beach and drowned himself. The timing wasn’t quite that poignant, but the fact remains that he was driven to a state of despair by the critical and unrelenting attack mounted against him by the foremost (and possibly only) newspaper of the day, The West Australian (still the only state based newspaper in WA). His other major critic and tormentor was the Premier of the state, John Forrest, though he was happy to share in the credit once it was a success.

I recently visited the weir for the first time in many years, and it was an occasion for reflection on its place in our history. Completed in 1903, it was the longest freshwater pipeline in the world at the time, the first to use steel pipes and fed by the highest dam in the Southern hemisphere. In 2009 it was recognised as an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers, only the 3rd in Australia and 47th in the world to be awarded, alongside the Panama Canal and the Golden Gate Bridge.

On a more personal level, I remember as a child we visited the weir often, as a family and as part of a youth group with a campsite nearby. I always found it interesting and it has a beautiful setting, surrounded by hills and jarrah forest. As a teenager, my family moved to a wheatbelt town, and the water we drank came from the pipe. The pipe ran under our front garden, though I hasten to add we didn’t have a tap connected directly, since the size of the pipe means it stands as tall as a person when it runs above the ground.

Not only had the pipe delivered water to the miners, it had also allowed the opening up of agricultural towns along the route. It is a constant feature running beside the roads, dipping underground to go through towns, then re-emerging on the other side. It is a guide; I can remember doing a walk-a-thon to raise money, and the route was simple. Just follow the pipeline, you can’t get lost! You can even walk on it if you feel adventurous and have good balance.

My recent visit also gave me pause for thought about our current environmental crises. Perth has traditionally relied to a large part on water from our various dams, but with climate change our rainfall has fallen considerably in the past 20 years. The last time the weir overflowed was in 1996, and visiting some years later it was sad and worrying to see the sloping gravel sides of the dam exposed by the falling water levels, a raw wound running around the circumference of the dam. It was a relief to see a much higher level last week, the water lapping the edge of the forest, but I was disillusioned to discover the pipe that pumped water into the dam from our desalination plant. I reasoned that it was necessary, as the weir still supplies Kalgoorlie and the towns on the way, but to me it was a tangible reminder that we in Australia were failing to take seriously the dangers of climate change. On the driest continent on earth, predicted to suffer most from a warming and drying climate, our politicians and right winged newspapers are happy to sabotage any efforts to address this urgent issue, preferring instead to criticise and lampoon scientists and concerned citizens, and to wilfully ignore the changes we see around us.

As I walked away from the weir lookout it occurred to me; things had not changed much since C.Y. O’Connor’s day.

My novel was inspired by our experiences when our parents emigrated with three children in 1964.

The wonderful thing about our new street was it had a library. With no television and only what we had brought in our suitcases, books were vital. We had no other possessions because our packing cases were still at Southampton Docks. Dad had made all our packing cases with rough planks from the timber yard; they were sent on ahead for their six week voyage, but there was a strike at the docks so they didn’t move. Mum and Dad had to eat into their capital to buy five of everything, bedding, plates etc. This was when we discovered peanut paste. Hard though it is to imagine a world without peanut butter, we had never tasted it in England and thought it was something exotic Americans had. In Perth it was called paste and came in jars that were actually drinking glasses; we had to eat our way quickly through five jars, lucky we loved our new treat.

The neighbours didn’t talk to Mum, except for a Dutch lady who introduced her dog.

He’s a Kelpie ( Australian sheep dog ) but mit the ears floppin down instead of mit the ears stickin up. Ever after, that was our term of reference for describing dogs.

The summer term was well under way in Australian schools. Children started at six years old, so though my five year old sister had already started school in England she could not go. She was so bored Mum kept sending her to the corner shop to buy one item at a time.

My seven year old brother could fit in with the right age group. I had already started at grammar school in England that September, now I had to go back to primary school. As Australian children started high school at twelve I could have ended up having to start another year of primary in January. Luckily I was put in Grade Seven and the teacher, Mr. Wooldridge, was excellent. He said it would be a disaster for me to be kept behind so determined that I would pass all the end of year tests. The maths setting out seemed to be back to front and upside down to what I was used to and of course I had no idea about Australian geography or history, but I got through. There are teachers who teach the work and teachers who talk to you about life and you always remember them. He told the dark World War Two story that I borrowed for Jennifer’s teacher in my novel, Quarter Acre Block.

The school was very different from my little Church of England junior school. No uniform, no school dinners; we just sat outside with our sandwiches, peanut past of course. The only other difference was the girls were a year older, more grown up and just liked sitting talking at break time instead of belting round the playground, but they were friendly.

We were still going down by the river, but I hadn’t learned to swim yet. The school summer outing was to Yanchep Park – everybody went on outings to Yanchep Park, about 30 miles from Perth; a very large nature reserve with a lake and caves. There was also a swimming pool and I had not told my class mates I couldn’t swim. Everyone was jumping in and I figured I could drop in and catch hold of the bar on my way down and cling on. I just went straight under, but luckily came up again, only to hear some snooty girl saying people who couldn’t swim shouldn’t be in the pool. I suppose it would have been even more embarrassing not to have surfaced.

School broke up before Christmas and we had six weeks holiday ahead. Dad’s search for a job and a house to buy was still on and the packing cases had not yet arrived.

What if I had been blogging when I was eleven…

My novel Quarter Acre Block is based on our family’s experiences as Ten Pound Pommies migrating to Perth, Western Australia, but is not autobiographical. Readers ask which parts are real? Some people say ‘weren’t your parents brave.’

Brave is going to a country with a different language or as an asylum seeker, being invited by the Australian government and given free passage with only £10 per adult to pay for administration costs, is not in the same league. Of course leaving your relatives behind and burning your boats with no job to go to and little capital is braver than staying put…

I needed my mother’s help to get the adult point of view, but the Palmer family are not my family. I wanted the story to be realistic, so the Palmers follow the same journey as we did. The ‘six week holiday of a lifetime’ sounded fun and I was envious of those who had come by ship, crossed the equator and met King Neptune, but the Palmer family had to fly.

I knew no one who had been in the migrant camps: I don’t think my father would have persuaded Mum to go at all if she had to face the prospect of a camp! She hadn’t been in the services during the war and had gone from home straight to marriage, so barracks and camps did not fall within her experience. Dad knew ‘someone from the office’ who had migrated and they sponsored us. The chap met us at the airport well gone midnight and as we drove across to the other side of the little city Mum was already looking out of the ‘station wagon’ in dismay. Once on our own, inside the caravan booked for us, she was soon saying ‘Rob, what have you brought us to’. We hadn’t seen much in the dark, but Mum had apparently focused on endless rows of electricity poles. Full of the whole big adventure I was exasperated that she was complaining when we had only been in Australia two hours.

The friend returned at nine am to take us down to Scarborough Beach. His family had taken to beach life and were living ‘the dream’. My younger brother and sister were terrified of the waves and I clung to a plastic surfboard, too embarrassed to tell their children I couldn’t swim. After that experience the only beach my parents wanted to sit on was Crawley Beach by the Swan River. It was very pleasant and Mum and Dad treated this first week as a holiday, we even had an ice cream every day, unprecedented, though it was not like Mr. Whippy and tended to have lumps of ice. Perth City was small then and you couldn’t get lost. Supreme Court Gardens were very pleasant and down by the Swan River was the wide open esplanade, so far we were living the dream.

After one night in the cramped caravan I had been despatched, or invited, I’m not sure which, to stay with the family of our sponsor. I was to be in the boy’s class at school and his younger sister did ballet, so I had nothing in common with her! I cringe now to think of my prepubescent self wandering around a house of strangers in my flimsy baby doll pyjamas, but all was above board.

After a week Mum and Dad had found a house to rent; as the venetian blinds were closed they didn’t see properly what it was like until Mum pulled the blinds up when we moved in. The only neighbour to speak to Mum was a Dutch lady. It was also time for me and my younger brother to start school, where their summer term was in full swing. This was nothing compared to the reality that Dad had to find a job and a house to buy and our packing cases were not going to arrive… more next week.

Read about the strange year leading up to our departure from England in last year’s blog.

https://tidalscribe.wordpress.com/2018/03/19/quarter-acre-blog/

Read more about my novel at my website.

https://www.ccsidewriter.co.uk/chapter-six-fiction-focus/

The words double glazing and salesman are inseparable, though there was a time when most folk had not heard of double glazing and salesmen had to go door to door selling vacuum cleaners. Perhaps long ago, glazing salesmen went round to castles and peasant huts trying to sell them the advantage of having panes in their windows instead of wooden shutters or pieces of old hessian.

In Victorian times householders in Scotland tried adding extra panes of glass to keep out the harsh winters, but modern double glazing started in the USA in the 1940s as ‘thermopane’ . Manufacturers began to use a vacuum between the two panes to improve insulation.

In the 1970’s it became popular for the domestic market in Britain and heralded the arrival of the double glazing salesman.

Meanwhile in Perth, Western Australia windows meant the necessity of fly screens. As new migrants with a new house my father made them himself and instead of closing the door to keep the cold out we children were always being reminded to close the fly screen door.

When I returned to England in the 1970’s for my working holiday ( the one I’m still on) it was to a country of three day weeks, power cuts and general mayhem. Pommies in Australia were congratulating themselves and vowing never to go back to ‘the cold’. When we left in 1964 fitted carpets were something posh people had, heating was something you lit and bedroom windows were covered in ice in the morning; beautiful patterns created by Jack Frost.

On Christmas morning I found myself in mild weather in the cosy little terraced house of my aunt and uncle. No one was cold, friends and relatives had central heating powered by North Sea Gas, carpet in every room and the cold kept out with double glazing. A popular topic of conversation was patio doors and porches; pretty French windows had been replaced by sliding doors and front doors were sheltered by tiny porches. I vowed never to turn into the sort of person who talked endlessly about porches and patio doors, or for that matter to ever be impoverished with a mortgage.

Not everyone had these home improvements. Our first flat had no heating, condensation running down the bathroom walls and washing and baby drying in front of the gas fire. But when we bought our first place, a tiny modern flat, our first Christmas was white and we were delighted with the central heating and double glazing.

When we bought an actual house it was the typical 1930’s tiny terrace that my parents had left England to escape. It did have that other popular home improvement, an extension across the back of the house, but this space was rendered useless in winter with cold draughts coming through the rattling doors and windows. We took out an impoverishing extension on our mortgage to get the whole house double glazed, but first had to decide which company. We set a record by having eleven companies come round to give a quote. The worst salesman asked if he could smoke (afterwards we asked ourselves why on earth we said yes) and sat there with sweaty armpits. We didn’t choose him.

But sealed double glazed units don’t last forever, if the seal ‘goes’ you can be left with windows that look like it’s always raining. Friends had the original aluminium picture window in their front room and for years you could not see out of it, there was a permanent mist.

Fast forward to the present; this is the longest we have lived in one house and we have gradually done some improvements and window replacements. The most recent being two back bedroom windows, a new porch and the living room window all scheduled to be completed in less than a week. We chose the local company everyone uses who had previously built our little conservatory, a blissful sun trap.

The two chaps who came out were loud and rude; I wasn’t sure if they were swearing at the windows or each other. When they said there was bad news, the front window was the wrong size, I thought they were joking, they weren’t.

With a holiday coming up and then seven visitors staying, the process has been drawn out. A different chap came out with the new window.

‘Are you on your own?’ we asked.

‘Yes, I’d rather work by myself, you wouldn’t believe some of the blokes I’ve had to work with.’

‘Yes, I think we would…’

He had hardly sipped the cup of coffee we gave him than he realised the windows were still the wrong size!

It has taken a while, but on Saturday at the third attempt we have a good window, nicely finished off by a chap and his son-in-law. Chatting with them we heard the first two blokes have been sacked as they didn’t get on!

We haven’t parted with any money yet, there is still a finishing strip missing from the porch, to be fixed tomorrow… I did suggest we say we can’t pay them as there has been a mistake with the money…

As I sat reading a book I felt and heard the reassuring rumble of the underground. But I was not on a London tube train, Mum and Dad were in the kitchen next door washing the dishes. We were in our little suburban house in Perth, Western Australia.

It was 10.59am, a bank holiday on the 14th October 1968, we had just experienced the Meckering Earthquake, my mother said she had to cling to the kitchen sink. The small town of Meckering was 130 km away in the wheat belt, the 45 second earthquake was magnitude 6.9 on the Richter Scale making it one of the largest recorded in the seismic history of Australia. A few buildings in Perth were damaged. A baby had a miraculous escape in Meckering, their town fell down, but no one was killed. Had the epicentre been in a big city it could have been a major disaster. For us it was exciting, proof that Man cannot control nature.

At school the next day the earthquake was the only topic of conversation. In the classroom we were all startled to feel an aftershock, this time we knew what it was and we were scared. The teacher told us to calm down. There was no evacuation or talk of emergency procedures. It was unlikely the one storey asbestos building would collapse dramatically.

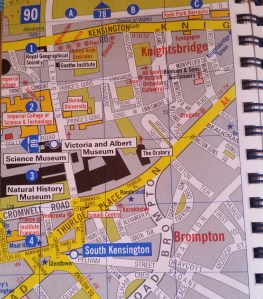

Fast forward to December 1974, Knightsbridge, London; I had a Christmas job as a floorwalker in Harrods toy department. It was the Saturday before Christmas and that afternoon I had the last tea break. The staff restaurant was on the top floor. As I stood in the Ladies combing my hair I heard a muffled thud and assumed it was an IRA bomb going off somewhere else. Of importance later was the fact that I had my handbag with me.

I walked out to see the busy shop deserted, the escalators switched off and a couple of security guards annoyed to see me still in the building, everyone else had been evacuated. Somehow I caught up with colleagues as we poured out of the building; it was only as we looked up and saw thick black smoke pouring from the corner of the iconic department store that the shock hit us. No one was hurt that day, the heroes were the staff who had noticed something suspicious in their department and evacuated customers safely. Heavy fire doors had contained the explosion. Once again I had had a wide escape. We sat in a nearby pub waiting to go back in and fetch our coats, but nobody would return to work that evening. Lucky for me I had my handbag with my season ticket for the train, even if the journey home was a bit chilly without my coat.

News is with us in all the media twenty four hours a day and this year fire, flood, hurricanes and earthquakes have been regular events and of a magnitude hard to comprehend. We wonder what it is like to be at the heart of a major disaster. Reporters find their way to the most unreachable scenes of devastation only to ask victims how they feel.

Back to Perth, Western Australia, when my fourteen year old self was riding her bike. The suburbs were laid out in a grid design with long straight roads, there was a ‘Give Way To The Right’ rule, logical as long as everybody obeyed; there were always accidents at intersections. I was pedalling towards a corner when suddenly two cars collided in front of me, one of them rolled over. The two young drivers clambered out with some difficulty, but both were laughing, unhurt. When I tried to get back on my bike my legs were shaking so much I couldn’t lift my foot onto the pedal. I have always wondered if everyone benefits from adrenalin when faced with real peril, or if some people turn to jelly. How many writers secretly long to be in the midst of a disaster and emerge unscathed, or just a bit hurt so they can tell their dramatic story from a comfortable hospital bed?

Grand Prix, everyday traffic – noise and pollution, I hate it, bring back the horse.

…but put big fuel guzzling engines up in the skies and I love them, carbon footprints forgotten.

I don’t fly often, perhaps if I did the novelty would wear off, but for me a trip abroad begins the moment the cabin floor starts to slope upwards and the engines blast into full power. A window seat and clear sky provide the fascination of identifying landmarks, but if the plane ascends through heavy cloud cover there is still the fun of being up in a fluffy heaven.

My first ever flight was across the world, when we emigrated to Australia. My novel ‘Quarter Acre Block’ was inspired by our experiences; in that story none of the Palmer family had flown before, but in real life my father had been a flight engineer in WW2. He was determined we would fly rather than sail out. I have flown across the world a few times since then, but perhaps more exciting was my shortest ever trip, flying in a light aircraft from Jandacot, Perth, Western Australia across twelve miles of Indian Ocean to Rottnest Island – real flying.

But mostly I have been on the ground looking up. At Farnborough Air Show, as children, we would marvel as jets flew silently by, followed several moments later by their sound.

Years later, living very near Heathrow Airport, we would spot four planes in the sky at a time coming into land, at night like ‘UFO’ lights. But the aeroplane we never tired of watching or hearing was Concorde. If many Concordes had been built and flown the noise would have been unbearable, but the two flights a day were an event; teachers in local schools would stop talking at eleven a.m., working in an airside passenger lounge with a great view of the runway, we watched her take off like a graceful bird. On winter evenings I would dash out of the kitchen into the garden to see her glowing afterburners soaring up. Alas poor Concorde…

The end of August brings the Bournemouth Air Festival, now in its eleventh year. If you don’t like the noise, are not interested in aeroplanes and live near the cliff top, there is no opting out, unless you go on holiday. Roads are closed, there are diversions, daily routine is disrupted as over a million visitors come over the four days. But this does not affect me. With visitors coming I have no intention of going anywhere except the kitchen, local shops and the sea front.

The longer the journey your visitors have made and especially if it is their first visit to the Air Festival, the more likely it is to rain. But with the festival spread over four days there is always some good flying weather. The cliff tops make ideal viewing and the beach is crowded. You can book a place on board a boat, but if the weather turns rough you are stuck out at sea! There are hospitality tents and deals at cliff top hotels with balconies.

It all starts tomorrow, so in next week’s blog I’ll fill you in on the highlights and weather, with hopefully some photographs.