Times and Tides of a Beachwriter is brought to you today by the colour peacock blue, thanks to Kevin Parish who started the ball rolling last week by choosing one of the most exotic colours. You can visit Kevin’s blog here.

Other birds may have streaks or patches of the iridescent blue, in tropical waters we might find fish showing off that colour, I don’t think any flower could quite match it. So the male peafowl gets to have a colour named after him. His home was originally India, he may have arrived in Britain with the Romans, but most of us think of peacocks strolling proudly around the grounds of stately homes. I like to imagine the lord of the manor bringing some home as a gift for the lady of the manor, but would she be so enamoured after constantly hearing their mournful cry? Perhaps she would suggest a banquet; their beauty did not prevent them being eaten, a dish to impress at mediaeval feasts.

Would any creatures from the past have worn peacock blue? I have never been to New Zealand, but it fascinates me because it was blissfully devoid of human beings until a thousand years ago or less. Reminding us that other creatures are there because they are there, not for us to go on holiday to look at or have documentaries made about them. Did the various species of giant moas have wonderfully exotic plumage, with no predators to worry about? But they did…

‘The Haast’s eagle (Hieraaetus moorei) is an extinct species of eagle that once lived in the South Island of New Zealand, commonly accepted to be the Pouakai of Maori legend. The species was the largest eagle known to have existed. Its massive size is explained as an evolutionary response to the size of its prey, the flightless moa, the largest of which could weigh 230 kg (510 lb). Haast’s eagle became extinct around 1400, after the moa were hunted to extinction by the first Maori.’

I wonder what sights greeted the first Polynesian arrivals on these remote islands. How sad moas are no longer with us.

Further back are the species that humans can’t be blamed for making extinct. What colour were pterodactyls? It is now theorised that dinosaurs were not the shades of greens and greys they are given in pictures. Imagine a peacock blue diplodicus or could you take an irridescent blue Tyranosaurus Rex seriously?

Can artists recreate peacock blue? Artists have always sought ways to make blue pigment.

‘ Lapis first appeared as a “true blue” pigment in the 6th century, gracing Buddhist frescoes in Bamiyan, Afghanistan. Around 700 years later, the pigment traveled to Venice and soon became the most sought-after colour in mediaeval Europe. For centuries, the cost of lapis rivalled the price of gold, so the colour was reserved for only the most important figures, such as the Virgin Mary and the most lucrative commissions, the church.’

The Winchester flower festival in the cathedral last year had as its theme the Winchester Bible, the bright red and blue flowers refelecting the colours used for illuminated text.

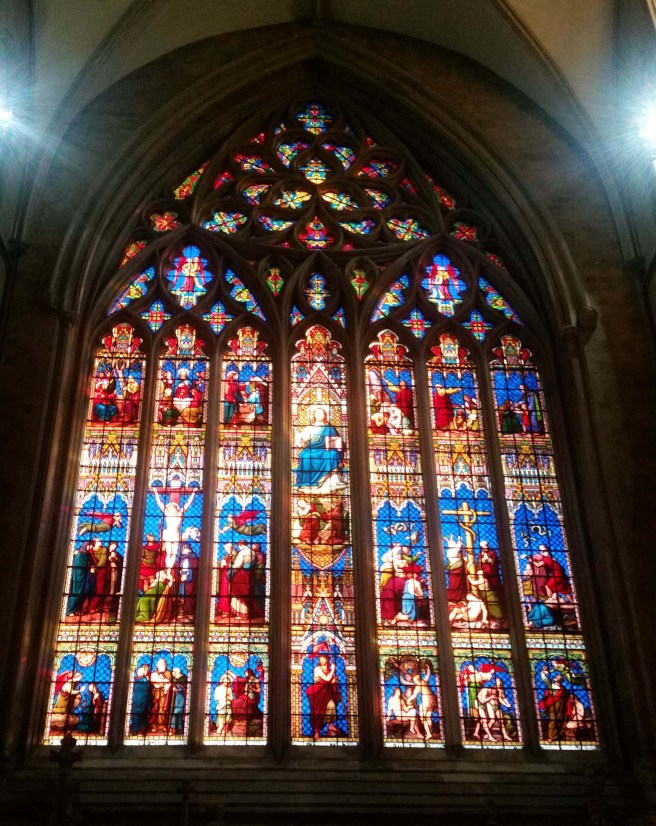

Or perhaps stained glass best recreates nature’s blue.

Next week’s colour, purple, was chosen by Sandra. If you have a favourite colour you would like to see, tell me in the comments.